Deceiving the Deceivers

Professor Salvatore Stolfo fights phishers with a taste of their own medicine

A series of conversations on pioneering research.

Sal Stolfo, professor of computer science.

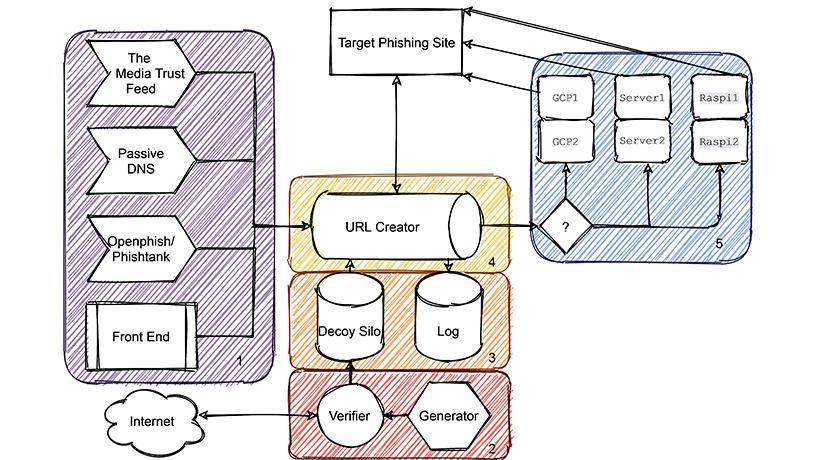

System architecture to deceive phishers.

When the FBI’s most recent Internet Crime Report named phishing as one of the top three concerns, that news came as no surprise to Salvatore Stolfo, professor of computer science. Stolfo has spent decades tackling some of the most difficult challenges in securing computer systems, earning more than 100 patents and launching multiple startups along the way.

Currently the primary means by which networks are breached, “phishing” refers to how attackers impersonate trust-worthy entities to trick users into revealing sensitive data—such as usernames, passwords, and credit card details—via deceptive emails, phone calls, text messages, and websites. Last year, it cost Americans $3.5 billion in losses.

What defines your approach to computer security?

The most vexing problem in computer security remains the human factor. Whenever you insert humans in any large computer system—from the design phase to the build phase to the deploy phase to the management phase to the user phase—security problems will emerge because of humans making mistakes or maliciously doing things that cause security breaches.

How does that insight inform your research on phishing?

The conventional wisdom is to train people not to fall victim to phishing, but phishers are just too good—training doesn’t work as e ectively as it needs to. My approach is to focus on building technology to make it harder for phishers to reach people. We essentially want to change the whole economics of phishing so that it’s no longer an activity without cost to the attackers.

And how do we best do that?

The best strategy for defending against phishing is to detect the phishing site when it first goes live. One way we do that is to stealthily embed a “beacon” in a company’s web page, so that when phishers make a wholesale copy of that page and try to pass themselves off as that company as a means of tricking people, they will copy the beacon as well. When the phishing site gets its first visitor, the beacon will go off, indicating the IP address of the server. If that server IP address is not the legitimate site’s IP address, we know a clone phishing site is active.

Once a phishing site is detected, there are a couple of ways of dealing with it. One is to take it down, but plenty of hosting services will not take it down, or they take too long to take it down. If that’s the case, there’s an exciting strategy we’re working on right now where we use deception against phishers.

Basically, we stuff a phishing page with bogus decoy information. When phishers grab data from ordinary users, they will have a set of real data and bogus decoy data. How do they know which is which? They don’t. And if they test the information to see what’s real and what’s not, we monitor the decoys we create so that we can gather information on the phishers, contributing to our learning about who they might be.

In essence, we’re trying to poison what they want to steal. It makes the economics of their malicious activity more costly for them.