Decoding Creative Thinking

Imagine a world where understanding how the brain makes snap decisions could help humans dramatically elevate their performance— alone, in teams, or even with robotic agents

Paul Sajda in the lab with research assistant Jennifer Cummings.

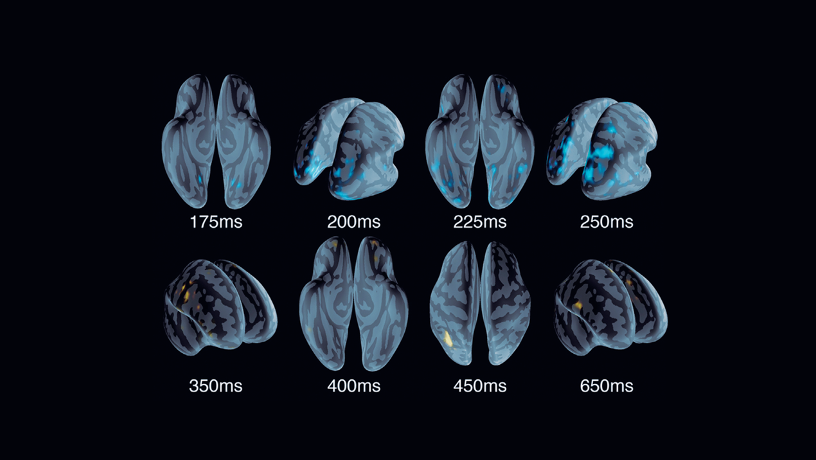

Spatiotemporal cascade across the brain when a subject makes a rapid decision about the category of an object just viewed

Scientists are only now beginning to understand how some of our most critical decisions get made in a split second. But fundamental questions still abound, and, particularly in high-stakes scenarios, we understand little about how our brains efficiently process a cavalcade of data. How, for instance, does a top athlete score a winning goal, an emergency worker navigate an evolving crisis, or a musician nail a live performance at Carnegie Hall?

“I’m really interested in how individuals or teams get really good at a certain task,” says neuroengineer Paul Sajda. “What is it about their decision-making process that generates this expertise?”

As a professor in the biomedical and electrical engineering departments with an appointment in radiology, Sajda’s interest in cognitive neuroscience has led to advances in neuroimaging and brain computer interfaces, including new techniques for measuring cognitive and physiological states that could help unlock the mental processes that foster elite performance, achievement, and creativity in various realms.

This spring, Sajda got a creative boost of his own. Named a Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellow by the Department of Defense—an honor bestowed on only 10 researchers a year—Sajda will soon branch his research off in new directions to explore “blue sky” ideas. Using virtual reality to test brain dynamics under conditions that mimic real-world settings, he plans to investigate a particular neural circuit connecting anterior, prefrontal, and middle regions of the brain in order to elucidate a key pathway for regulating cognitive control and arousal states. Findings could improve not only team dynamics, but also how AI agents can “think” more like humans and interact as valuable members of teams.

A major application is already in the works. Sajda has partnered with computer scientist and fellow Columbia engineer Dan Rubinstein to investigate emotional distress in first responders in an effort to promote better communication and more effective resource allocation across teams during a crisis.

As our knowledge of the brain improves, Sajda believes emotionally intelligent robots and more self-aware teams could unleash unlimited possibilities for impact and creative solutions.

“We can reconfigure teams so that they become dynamic and maximize performance,” says Sajda.